Looking down on creation

Every morning the sun has to climb an entire mountain before smacking my doormat. Haleakala has gripped me nearly all my life like a magnetic giant. Here in Keokea, it’s as if I am sitting in the giant’s breast pocket.

The nearest shore is eight miles away and almost 4,000 feet below—and I can see it clearly. I see the island’s two great bays pinching the central valley. I see sharp-ravined West Maui with its shifting headdress of cloud. To the left there’s the soft, tawny dome of Lanai, then the little scimitar of Molokini, then, best of all, right out my office window, the vivid red hide of Hawaii’s spiritual heart, Kahoolawe.

The best day I can ever have is to stay at home all day. Watch and think.

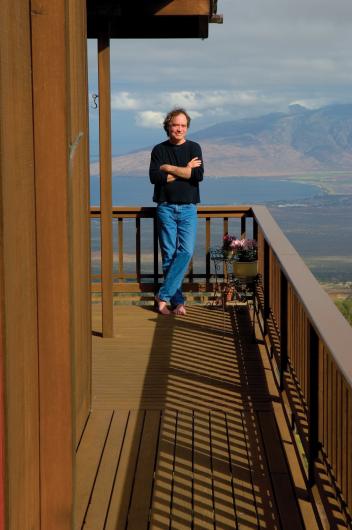

After the sun completes its arc overhead, it explodes noiselessly into a sky-wide extravaganza that we inadequately label “sunset.” You will often find us at that hour standing on the lanai clap- ping and whooping and shooting futile photographs.

Of course, after the sun goes down, outcome the moon and the planets. We see the jets from Honolulu drifting below us and disappearing into the growing jingle jangle of Maui’s urban illumination. The lights from the Safeway in Kihei are as bright as a ballfield.

Even on Maui, lots of people have never heard of Keokea. The post office con- siders this to be Kula. I resent that. We are farther out than Kula—in both senses of the phrase. To live here, you have to have an outcast mentality—or be third-generation Chinese.

The Chinese settled here in the early 1800s, converting the native Hawaiian sweet- potato plots to the production of white potatoes, which they then sold by the thousands to whaling ships and California Gold Rush miners. The names Fong, Ching and Hew are common here. There’s a statue of Sun Yatsen in a shabby little nearby park. The brilliant Chinese revolutionary’s brother owned a cattle ranch here, where Yatsen found refuge on several occasions.

If not Chinese, it helps to be a character. Several of Maui’s best artists live here. So does the marketing genius who launched the Dockers pants line. So does a Gaelic piper who gathers his bagpipe-playing friends now and then to fill the mountainside with reels and airs. As the sun sets, a pueo, or Hawaiian owl, flies past our windows, muscling along like an Olympic oarsman, cocking his head for an indifferent glance as he goes.

Ironically for a place where the views are so splendid, Keokea’s defining feature is its frequent fog. I don’t mean mist. I mean peasoup stuff like you think you never find in Hawaii, fog that swallows the house, so thick it sends visible tendrils writhing into the living room.

This whiteout results from a cloud. Often, a very dense cloud comes up against this place on the mountain and sticks. This cool cloud explains why people traveled uphill across eight arid miles of scrubland from the coast, in order to farm potatoes. It also explains the name “Keokea,” which refers to whiteness (kea) and some says means “white sand,” though there’s none of that here. I think it means something like “a bold protrusion of ever-whitening whiteness.”

When the fog encloses the house, the owl still wings past, navigating by sound. When the fog lifts, it’s like looking down on creation from God’s carport.