Nearly two centuries after O‘ahu’s Governor Boki Kamā‘ule‘ule introduced the first fragrant beans to Hawai‘i, coffee has taken root on all the major islands. But from a traditional 20-acre farm to a 3,100-acre agribusiness—the largest coffee farm in the country—no two have the same story to tell.

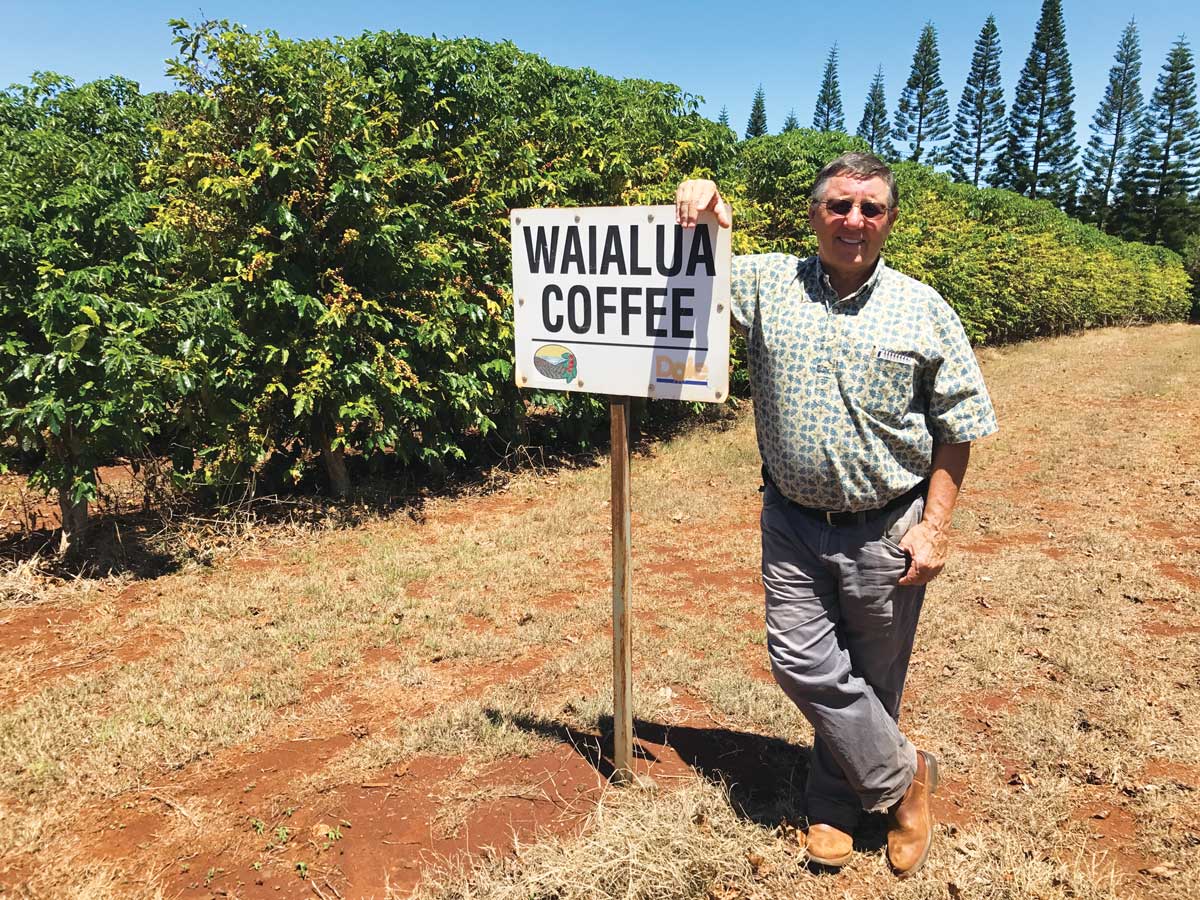

WAIALUA ESTATE COFFEE & CACAO

Watching the coffee berry borer ravage harvests across the Big Island, Mike Conway of O‘ahu’s Waialua Estate Coffee knew it was a matter of time. The elusive bug is difficult to defeat and good at spreading. Intensive efforts tailored to Kona’s smaller acreages and sloping, hand-harvested fields were lowering infestation rates there, but what would agribusiness executives like Conway do when CBB reached their bigger, mechanized fields? “I hated it when we got it first. I would have preferred somebody else to get it so I could see what they were doing,” says Conway, longtime manager at the Dole Diversified Agriculture subsidiary. But “we are the first mechanized operation that has to deal with this thing, so everybody on the other islands is watching how we are managing the bug and still get by. We have to make up our own strategy and keep going. It’s not easy.”

CBB appeared in Waialua in 2014, four years after it was first reported on Hawai‘i Island. How it apparently skipped fields on Maui and Molokai and chose to infest his, Conway will never know. In the years since, he watched CBB take hold in as much as 28 percent of his crop. On the 110 infested acres of his 155 total, Conway turned to traps to identify areas where the bug was most plentiful. On humid, overcast or slightly rainy afternoons when the female bugs emerge from the coffee berries and swarm in search of new ones to bore into, crews spray the beauveria bassiana fungus. Then, “We take about one quarter of the farm each year, 30 to 35 acres, and we stump the trees, remove every last bean, clean it up and start clean again. Then the next year we do another 30 to 40 acres, so about every 4 or 5 years we stump our trees and start over again,” Conway says. “The second year after you stump you don’t get much coffee, so it really amounts to about 60 acres each year we take offline.”

Conway hears other coffee growers strategizing about less intensive ways to control the bug when it hits their fields, ways that won’t affect production much. At one point he was hopeful, too. But “you get kicked in the head a few times, you learn,” he says. The combination of intensive spraying and stump-pruning has brought Waialua’s infestation rates down to 10 to 11 percent. Against CBB, those are manageable numbers. It makes Conway cautiously optimistic. And it makes Waialua Estate Coffee a notable model for the rest of the state’s big growers.

MAUIGROWN COFFEE

If Mike Conway is optimistic, Kimo Falconer is even more so. It’s 14 years now since Falconer resurrected the Ka‘anapali Estate Coffee operation shuttered by his former employer, Pioneer Mill Co., and 13 years since his MauiGrown Coffee produced its first crop. Now, with four varieties of arabica growing well on 400 acres in West Maui, Falconer has his eyes on the next chapter: an expansion out of Ka‘anapali for Hawai‘i’s second-largest coffee grower (Kauai Coffee is first).

For MauiGrown, that would be Chapter Four. The first goes back to sugar, when the fields in sunny, drier Ka‘anapali were planted in cane. Chapter Two, from 1988 to 2001, sees some of the land converted to coffee production, with Falconer working as Pioneer Mill’s director of agricultural production. In Chapter Three, the company has abandoned coffee as unprofitable and Falconer returns as savior and visionary, determined to turn the fields into a viable operation that will put Maui estate coffee on the world map. The trees are all drip-irrigated from century-old sugar plantation ditches flowing down the mountainsides, and planted hedgerow-style—36 inches apart in rows 12 feet apart—to allow for mechanized harvesting. Experiments with different types of arabica narrowed the results to four—Yellow Caturra, Red Catuai, Guatemalan Typica and the ancient varietal Mokka—that grow well in different parts of the terrain. The last makes up just 15 to 20 percent of the harvest, but Maui Mokka, which took top honors at the Hawai‘i Coffee Association’s statewide cupping competition in 2014, is the company’s pride.

Since last year Falconer has been trying to expand the operation into central Maui. The 36,000 acres that went fallow when Alexander & Baldwin closed Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Co. in 2016 have fired his imagination. “We’ve got a thriving operating business that I’d like to expand,” he says. “Think of China and all these emerging markets. Starbucks has announced they’re going to open 1,000 stores. It’s a great crop. It’s vibrant. I see the market becoming bigger and bigger and it could be really good for Hawai‘i.”

MELVIN KUNITAKE FARM

On the sun-drenched slopes of Hualālai, on the land where his parents and grandparents planted coffee, Mel Kunitake is a living link to coffee’s local past. His 20 acres stretch from 800 to 1,100 feet in elevation, some carved out of lava fields, some coated comfortably in soil. “I don’t think I’ve seen anything on other islands comparable to what we have here,” Kunitake says. “My grandparents dug holes in the lava fields, one to two feet deep, to plant coffee trees. It’s kind of amazing to think what people went through.” Like many early immigrants on Hawai‘i Island, Kunitake’s grandparents finished their sugar plantation contract and ended up leasing, then buying and farming their own land in Kona. Many planted coffee and began the cycle the 83-year-old Kunitake still lives by today. Modernization came, though not as much as the family would have liked. When they got electricity, they switched from drying beans on the rooftop to a mechanical dryer. But attempts at drip irrigation in the lower, drier fields were thwarted by wild pigs who chewed through the tubing, and the mechanized harvester Kunitake’s father bought was defeated by the rocky slopes and eventually ended up on more level fields on Kaua‘i.

“Coffee picking is all manual labor,” Kunitake says, a point of view you hear mostly on this island, because world-famous Kona and Ka‘ū coffees thrive on cool slopes under afternoon cloud cover that can drench the fields. Machines get stuck in the mud; human pickers don’t. But where in his youth it was family and local hires who pitched in during harvest season, finding seasonal labor these days is one of Kunitake’s biggest issues. He’s hired crews from Honduras, Thailand, Peru, Micronesia and Mexico. Ironically, this same hand-picked aspect also helps elevate the quality of his coffee: Instead of stripping branches—which can take off green, ripe and overripe berries—workers pick only ripe coffee cherry, then cycle back to collect more as they ripen, over and over through the season.

In 2015 this cycle made Kunitake a poster child for 7-Eleven Hawaii. The chain began buying all the freshly picked coffee cherry he sells to a processor, designating Melvin Kunitake Farm as the single source for the Kona beans in its Estate Roast 20% Kona Blend coffee. This for a man who continued the family tradition not because he wanted to grow coffee, but because it was his duty to help put his six younger siblings through school. Kunitake worked at the farm without pay for 20 years. “I never intended to be a coffee farmer,” he says, “I just ended up inheriting part of the industry.” While several siblings and cousins still farm coffee in Kona, Kunitake’s daughters aren’t interested in taking over their father’s farm, so he knows he’s likely his family’s last connection to this land. Which makes the fact that his coffee is now all over Hawai‘i, after three generations of lifelong hard work, a fitting and deliciously bittersweet coda.

RUSTY’S HAWAIIAN

When Rusty Obra passed away in 2006, for his wife Lorie, continuing the farm they started was about self preservation. “Taking care of it was the one thing that gave her life purpose,” says Joan of her mother. Rusty and Lorie had begun their 12-acre farm on the southern slopes of Mauna Loa in 1999, when Ka‘ū was a brand new coffee-growing region. Rusty, who had wanted to make the area as famous as Kona for coffee, died just a year before awards for Ka‘ū farmers began coming in. Buoyed by success, Ka‘ū’s coffee acreage has increased by 30 percent over the past decade, and under Lorie’s watch, Rusty’s has been garnering attention from cupping competitions to The New York Times.

Before farming, Lorie had worked as a medical technologist, and she turned her scientific mind to coffee processing, experimenting on coffee from harvest to the green bean (unroasted) stage, pushing what was possible or known. She’s never been afraid to try methods that sound outlandish, like fermenting the cherry in pineapple juice, Pepsi and even saltwater. She’s learned to adapt her processing to the varietal, weather and customer preferences. A decade of experimentation prepares her for agility, as the caffeine-fueled industry constantly shifts to adapt to current trends and future challenges. Some of the trends are for the sake of curiosity in an increasingly savvy specialty-coffee world—say, fermenting with yeast, as with beer and wine. Others are practical: There’s a growing interest in natural-processed coffees, as people are more concerned about water usage. (Natural coffee requires less water, but washed coffee is a faster process yielding more consistent results.)

Ka‘ū may be a relatively new to coffee, but its fears are the same as other, older regions in the world. Rusty’s currently manages to control CBB thanks to diligent management and its isolation from other farms, but it worries about the arrival of coffee leaf rust, a rust that has killed entire fields in a matter of weeks and shut down farms across Latin America. And for an extremely temperature-sensitive crop, there’s the specter of climate change. The farm has a little more lead time than others though, as Hawai‘i sits on the northern edge of the coffee belt and Rusty’s at about 2,000 feet, a relatively high elevation for coffee. Meanwhile, as researchers try to develop new varieties that taste good and are resistant to rust and warmer temperatures, Rusty’s continues to tinker and grow alongside the Ka‘ū coffee industry.

KAUAI COFFEE COMPANY

Since late September, when harvesting began at the largest coffee farm in the U.S., it’s been going around the clock, seven days a week. For roughly three months towering machines will rumble down the rows of coffee shrubs, shaking the beans from the branches and transferring them to trucks waiting to take them to the factory—12 million pounds of cherry in all, about 5,500 pounds per acre, if Fred Cowell’s estimates come in on target. This is when Kauai Coffee Company’s normal payroll of 135 farm, factory, maintenance, sales, visitor center, roasting plant and administrative staff swells by another 50. “It all tends to ripen at once and we have to be able to bring it out when it’s ripe,” says Cowell, the general manager. “At night it’s a little bit cooler and our machines are operating with overhead lamps on the harvesters.”

It’s a little over a year and a half since Cowell, the 58-year-old son of longtime Kona coffee farmer Skip Cowell, took over the operation. Before that he did infrared research on Kaua‘i, before that he spent 20 years in the Air Force, and he also sold coffee real estate in Kona. He still knows the approximate acreage of many of the 800 to 900 small farms arrayed along the slopes of Hualālai and Mauna Loa. Even before that, expecting to follow in his parents’ footsteps and take over the family farm, he majored in business, got a master’s degree in international relations and even studied Japanese, thinking he would sell his coffee in the Japanese market.

Instead Cowell ended up on the other side of the state, bringing his new-generation ideas and Kona coffee upbringing to Kauai Coffee’s 3,100 converted sugar acres in Eleele, Kalaheo and Poipu. He’s focused on three goals: increasing sustainability, leveraging technology and raising overall quality. He’s improving soil conditions by introducing cover crops, composting, even shade trees. “When people ask me what’s the key to coffee quality, in my opinion it’s soil first, coffee variety second, and processing method third,” he says. “Now we’re looking at sensor technology, flying drones to map fields and trying to optimize irrigation so the soil will tell us when to water. We’re basically using precision agricultural techniques within the coffee world—which is not usually done because there aren’t many farms on our scale.”

Many of the ideas have been brewing in Cowell’s head for a while. It’s only natural, he says. “Why? Because they hired a Kona coffee farmer to come take over.”