Experience cowboy culture, and more, in Waimea, Big Island’s ranch town

In Waimea, Hawaii, you’ll find cowboys and cattle, plus farmers, restaurateurs, astronomers and everyday folk in love with its beauty.

The sign on the post office calls it Kamuela, but the 8,500 people who live there call it Waimea.

The Big Island town, nestled between the Kohala Mountains and the slopes of Mauna Kea, is easy to confuse with other places in Hawaii. Kauai’s fabled Waimea Canyon and Oahu’s equally legendary Waimea Bay, while nowhere near the town, share its name.

But, as fascinating Hawaii places go, Waimea, with its rolling green hills and vistas, holds its own with the best of them.

Waimea was home to cowboys before the American West was born. In 1793, just down the road at Kawaihae Harbor, British sea captain George Vancouver gave a herd of five cattle to Kamehameha the Great. Under a kapu (taboo) for their first few decades, the longhorn cattle multiplied, ran wild, trampled crops, hurt and even killed people.

Enter John Palmer Parker, a 19-year-old seaman from Massachusetts, who jumped ship on the Big Island in 1809. Parker eventually became Kamehameha’s wild-cattle hunter, selling salt beef to passing ships.

By 1832, three Mexican vaqueros were brought to teach the Hawaiians how to herd the cattle with horses. (Vaqueros would later do the same for the cowboys of the American West.) Hawaiians transformed español, the word for Spanish, into the word paniolo. New meaning: cowboy. Waimea’s ranching tradition was born.

Photo: David Croxford

Parker married one of Kamehameha’s granddaughters, Chiefess Kipikane. His family, now Hawaiian aristocracy, grew Parker Ranch into the largest ranch in the state, drawing frequent visits from the reigning monarchs. It was King David Kalakaua who first called the town Kamuela—the Hawaiian name for Samuel—after Parker’s prominent grandson, at one time foreign minister of Hawaii.

The new name didn’t quite stick, but the town grew in importance. A community trust now owns Parker Ranch, which has 20,000 head of cattle on 150,000 acres. Waimea is dotted with other ranches, including the innovative Kahua Ranch, where we were privileged to be invited to photograph the yearly cattle roundup.

Still, over the years, Waimea has become more than a ranching center. It boasts dozens of productive farms—which have made the little town something of a culinary center—numerous restaurants and three bustling farmers markets.

In addition, Waimea town has three theaters, a full-service, acute-care hospital, an internationally-renowned private school, a Grammy-winning recording studio and a significant art gallery.

Thanks to the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy’s telescope facilities on the summit of Mauna Kea, Waimea has also become a world-class science center, drawing astronomers from all over the globe.

When people from somewhere else dream of the perfect Hawaii spot, they think of white sand beaches and palm trees. When people in Hawaii dream, they often long for cool, green, rolling hills dotted with cattle, and a town where the past and the vibrant present meet under the soaring vista of Mauna Kea.

Welcome to Waimea.

Wild west heritage

Under the pressure of the recession, Parker Ranch shut down its museum, visitor center and all visitor activities.

But Waimea’s ranching past refuses to fade away. Here, Anthony Roberts, the General Manager of the Paniolo Heritage Center (67-139 Pukalani Rd., Kamuela, (808) 854-1541, paniolopreservation.org), shows off Pukalani Stables, which bred horses for Parker Ranch and, until World War II, for the U.S. Cavalry. A young cavalry officer named George Patton once traveled to Hawaii to pick out his own horse here.

Derelict since the 1970s, the stables were leased by Parker Ranch to the Paniolo Preservation Society, and the nonprofit has turn the stables into a visitor center and museum.

“I’m from Texas,” says Roberts. “There we have only recreated, almost Disneyland versions of our cowboy heritage. In Waimea, the Wild West never went away. It’s all right here.”

Hawaiian style eats

The place is small and homemade looking. The dishes are plastic. The décor seems random. But Hawaiian Style Café (65-1290 Kawaihae Rd., Waimea, (808) 885-4295, hawaiianstylecafe.us) may be the ultimate local-style eatery in the Islands.

The loco moco, so big it fills a platter, is legendary, but we’d suggest the teri-beef burger-chicken cutlet plate lunch, pictured here. We’ll bet you can’t finish it.

Last roundup

It’s shortly after dawn during Kahua Ranch’s (808) 882-4646, kahuaranch.com) last roundup of the year. A calf escapes from the branding pen, meaning that three paniolo have to ride down the sloping pasture and corral the reluctant calf once again. After all 225 calves are branded, castrated and treated, they are allowed to roam freely through the fields for summer grazing. Kahua Ranch modern paniolos often ride the range in ATVs, but situations like this require the skills that Hawaiian cowboys have been using for generations, nimble horsework and roping skills.

Waimea in bloom

Everything grows in Waimea, it seems. Bob and Jennifer Snyder raise two greenhouses of Cymbidium orchids, their showy blossoms a riot of reds, browns, purples, oranges, yellows and greens, many striped or speckled.

“There are 30,000 species of orchids,” says Bob. “The oldest recorded genealogies are for racehorses and orchids.” The Snyders raise exotic hybrids on their Waimea farm with equally exotic names like “Hot Mouse by Dorothy Row.”

They’ve spent five years creating their own crosses. “That one over there, I can’t wait to see how it turns out,” says Bob.

As Orchidpeople of Hawaii (808) 885-5589, orchidpeopleofhawaii.com), the two sell 2,000 to 3,000 cut orchid stems a year, usually with a dozen or more blossoms, plus 3,000 potted orchids. “The Big Island is the Orchid Isle,” says Bob. “What else would we grow?”

Farm to table

Of the dozens of farms scattered throughout Waimea, perhaps the most beautiful is Hirabara Farm. Red and jade-green baby lettuces, heirloom tomatoes, fingerling potatoes and white asparagus, all pop up in neat rows from the volcanic soil.

“We’re low-acreage high-yield farmers,” says Kurt Hirabara, a soil scientist who moved to Waimea with his wife, Pam, in 1995. “We know what we’re doing.”

“Well, Kurt likes to think we do,” quips Pam. “But, really, we can grow almost anything a chef could ask for.”

Chefs respond to Hirabara’s wares with fervor. One wall of the farm’s packing shed is scrawled with chefs’ autographs: Mario Battali, Jonathan Waxman, Michael Shapiro and almost every Hawaii chef of note. Our favorite autograph? From James Beard Award-winning Hawaii chef Alan Wong’s mother: “I taught Alan everything he knows.”

Food for the soul

Another window into Waimea’s ranching past is Anna Ranch Heritage Center (65-1480 Kawaihae Rd., (808) 885-4426, annaranch.org), until 1995 the home of a third-generation rancher, Anna Lindsey Perry-Fiske. Born at the turn of the 20th century, Perry-Fiske was “the first lady of Hawaii ranching.” The ranch buildings, now on the National Register of Historic Places, have been fully restored, with a gift shop, ranch tours and a blacksmith and saddlemaker in residence.

Anna Ranch also hosts a Wednesday afternoon farmers market.

From ranch to stage

Richard Smart, the sixth-generation heir to Parker Ranch, had an unexpected career: musical theatre. He sang on Broadway and in cabarets around the world. When, after 30 years, he returned to Parker Ranch to live, he brought his love of theatre back with him. In 1980, he built Kahilu Theatre ( 67-1186 Lindsey Rd., (808) 885-6868, www.kahilutheatre.org) for the community.

The 490-seat theatre is now a nonprofit foundation. It hosts ukulele festivals, classical performances, jazz, world music, plays, musicals and dance recitals, including a full program of free performances for students and the community at large.

Here, the Philadelphia Dance Co.—known as Phildanco!—wows an audience of local schoolchildren.

With cowboys came guitars

Waimea is an unlikely place for a major recording studio. But slack key guitar was born here, when Mexican vaqueros first brought guitars to Hawaii in 1832. Here master guitarist Charles Brotman writes, produces and records music—his own and others.

Brotman has recorded everything from dialogue replacement for Hollywood movies to hip-hop. But his main love is acoustic guitar.

“I wanted a studio where a recording sounded like someone was playing right in front of you.”

Brotman’s own label, Palm Records (808) 887-0107, www.palmrecords.com) produced the first album ever to win a Grammy Award for Hawaiian music.

“I can’t imagine living anywhere else but Waimea,” he says.

Eyes on the sky

The observatories atop Mauna Kea have mankind’s best view of the cosmos, but conditions at the 13,796-foot summit are so difficult that most the real research is done at remote facilities at lower elevations—some of it in Waimea. Here, astronomers at Waimea’s W.M. Keck Observatory (65-1120 Mamalahoa Hwy., (808) 885-7887,www.keckobservatory.org) watch readouts and images from Keck II, one of Keck’s two giant telescopes atop Mauna Kea. Astronomers worldwide compete to get a night or two to use the scopes. They are aided by Keck astronomers like Marc Kassis, who says, “I absolutely love this job. Astronomers come here from all over the world. Many nights, I’ll hear, Marc, Marc, come look at this! Someone has found something totally new.”

Waimea memories

Charlie and Barbara Campbell—who now run a comfortable bed-and-breakfast called Waimea Garden Cottages (65-1632 Kawaihae Rd., (808) 885-8550, waimeagardens.com)—arrived in Waimea in 1965. “Back then,” they recall, “the paniolos’ dogs would sleep right in the middle of the town’s main intersection, because the asphalt was warm. You’d have to drive around them.”

Charlie is a retired large-animal vet, and Barbara was sales and marketing director of the Kona Village Resort, which for many years had no road. She commuted by small plane to the resort’s private airstrip.

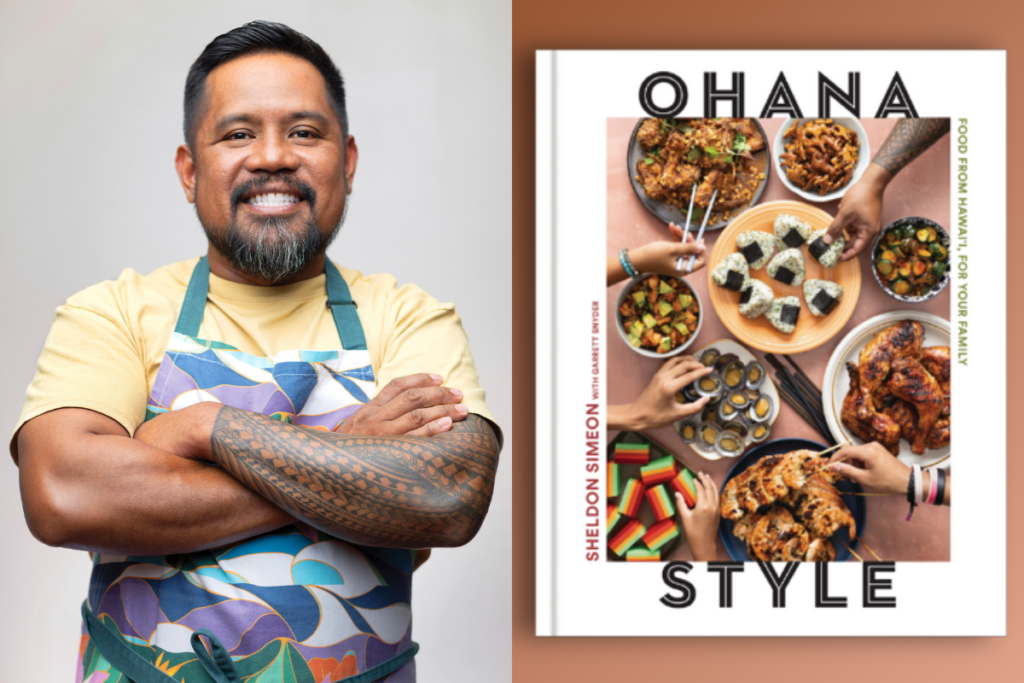

Culinary pioneer

In 1988, Peter Merriman left the Mauna Lani Bay Hotel, where he’d been the youngest executive chef in the Islands. He moved up the mountain to Waimea and started a restaurant with a concept that many at the time thought was daft: He would use as much local meat and produce as he possibly could. Merriman cultivated farmers and ranchers and began a culinary trend that culminated in Hawaii regional cuisine.

These days, almost every restaurant tries to be farm-to-table, but Merriman’s in Waimea (65-1227 Opelo Rd., (808) 885-6822, www.merrimanshawaii.com) has been at it longer and still does it best—procuring quality local ingredients, from spinach to wild boar, and simply letting them shine.

Art on the range

Waimea’s Isaacs Art Center (65-1268 Kawaihae Rd., (808) 885-5884, www.isaacsartcenter.hpa.edu) contains an unexpected trove of Hawaii art. There are contemporary shows—like the Hawaii Wood Guild’s annual exhibit—and a gallery of masters from earlier centuries. The center is owned by neighboring Hawaii Preparatory Academy, a nationally recognized private school at the foot of the Kohala mountains.

The art center building is itself noteworthy. Built in 1915, it once housed Waimea’s first public school, and was rescued from demolition and repurposed. The building still has the sliding pocket doors that once divided classrooms. Open the doors and you can still see the class blackboards.