Bishop Museum exhibit displays a Hawaii that never was

Vintage memorabilia, on display until January 2019, immerses viewers in popular Hawaii stereotypes.

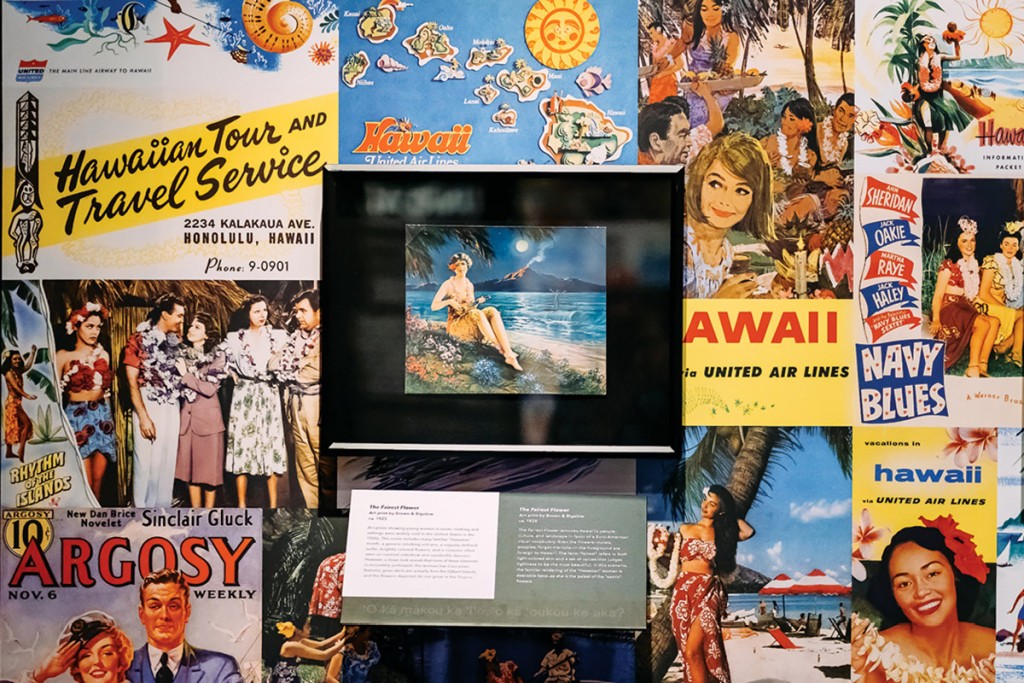

Thinking critically about how Hawaii has been falsely presented to the world is what the Bishop Museum hopes visitors will do while perusing its new exhibit, “Unreal: Hawaii in Popular Imagination.”

Colorful illustrations, depicting the Islands from the 1930s to ’60s, fill the walls of the museum’s J. M. Long Gallery. They are examples of fake representations of Hawaii, and come in the form of advertisements with smoke billowing out of the long-extinct Leahi volcano (aka Diamond Head), books, magazines, sheet music and “Hawaiian” restaurant menus that feature pineapple, though the fruit originates from South America.

“It was the desire to give context to these images,” says Bishop Museum culture educator and exhibit committee member, Kapalikuokalani Maile. “Not only where they come from and some of the history, but also to provide some interpretation about how these images have been disseminated around the world and how there are consequences about what these images do, in terms of representing Hawaii as a place and often Native Hawaiians as a people.”

A food and cocktail recipe booklet from 1943 sits behind a glass case titled, “Here’s How in Hawaiian Hospitality,” with a woman supposedly personifying hospitality. Standing atop a map of the Islands in a strapless bikini top and grass skirt, she’s holding a glass in one hand and a tray of fruit in another, while the wind lifts her lei and skirt to show more skin. “Our hostess spreads her legs over and treads upon the Islands, poised to offer a feast for consumption. She is an exotic hostess, available to satisfy with food, alcohol, and perhaps anything else a visitor might desire,” the interpretive sign reads. “Through blatant sexual objectification, Hawaii is transformed from a distinct and complex land, people and culture to an object sold as a willing commodity under the guise of open hospitality.”

The artificial and unauthentic image of women wearing strapless bikini tops with shiny grass skirts is in almost every illustration—and one life-size hula costume worn by Pualani Mossman Avon, who danced in The Hawaiian Room at the Lexington Hotel in New York City circa 1930s-40s, hangs inside a display case. Half-dressed women are also seen on covers of romance novels, such as It Happened in Hawaii and Hawaiian Caress, and comic books, as seen in the Archie series’ Veronica in Hawaii. On a Life magazine cover, a man in a suit looks longingly at a hula performer, while a woman dressed conservatively in a long skirt and jacket, who you’d guess is his wife, stands behind him watching. In comparison, Native Hawaiian men are rarely seen, except on surfboards teaching female visitors how to surf in front of Diamond Head.

“Visitors who are interested in the discussion really have to visit the exhibit to be immersed in the images,” says Maile. People who aren’t familiar with those times “can see the real variety of ways that Hawaii has been depicted through the past and how some of those things have consequences for how Hawaii is understood in the present time as well.”

In another illustrated piece, a sailor and young Hawaiian hula girl stand together arm-in-arm, as if posing for a photo, on a piece of sheet music from 1925 for the song “Gob,” a slang word for sailor. “In American society, interracial relationships were taboo, and laws in many states outlawed them. Hawaiians fell somewhere in the middle,” the interpretive sign reads, immediately changing the perceived reality. “This perspective allowed for the visual display of escapist interracial romances depicting only fleeting and inevitably doomed relationships between white men and Hawaiian women.” However, this wasn’t socially acceptable at the time between white women and Native Hawaiian men, it goes on to say.

Juxtaposed on the other side of the gallery is a 20-foot-long, two-sided mural titled “‘Aina Aloha” (“Beloved Land, Beloved Country”) that provides a Native Hawaiian perspective of Hawaii’s traumatic past and hopeful future. The project, spearheaded by artist and filmmaker Meleanna Meyer, features the work of six Native Hawaiian artists who spent 400 hours painting expressions of emotions over the indigenous people’s loss of land and the silencing of their language and culture.

“On one side [of the mural], you have Native Hawaiian culture represented—it’s a thriving culture—there are particular subjects and symbols that are really intrinsic to Native Hawaiian practice,” says Maile. “And the other side [of the mural], which is more abstract, you have elements like hands reaching out, you have different kinds of colors, like red. One side is intended to show the flourishing, the living of Hawaiian culture and practice, and the other side gives a visual way of representing eha, pain, tragedy, and what it has meant to be Native Hawaiian in Hawaii.” It stands as a real representation of Hawaii and all its complexities amidst a gallery filled with unreal imagery of Paradise.

“Unreal: Hawaii in Popular Imagination” is on display now through January 27, 2019. Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice St., Honolulu, Oahu, (808) 847-3511, bishopmuseum.org.