Kamaka Hawaii celebrates 100 years of handcrafting ukulele

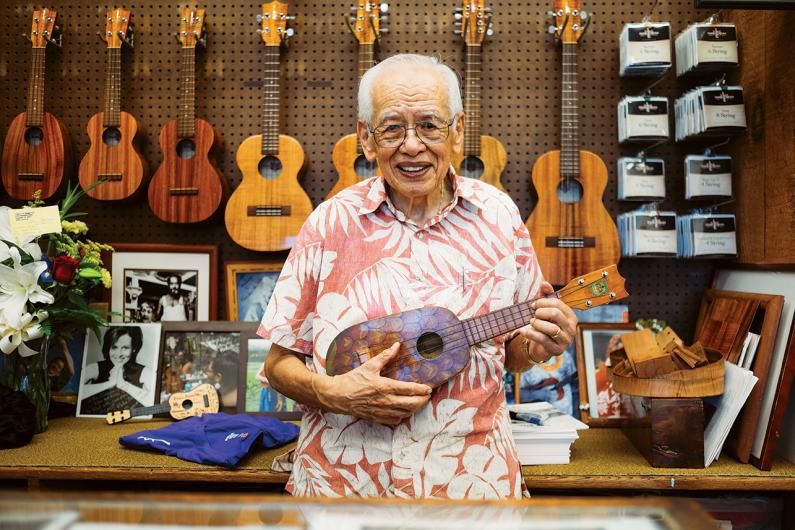

Standing behind the counter of Kamaka Hawaii’s Honolulu store, Fred Kamaka strums through each of the nine ukulele hanging on the wall next to him, and the conversations of the people chatting around me fade away. It’s the signal that the factory tour is about to begin.

Photo: Aaron Yoshino

Fred is the 91-year-old son of Samuel Kamaka, who started this business in 1916. Fred and his brother, Sam Jr., learned how to make ukulele at a very young age, helping their father since its early days of operation, creating and continuing a long multi-generation legacy for their family while becoming major contributors to Hawaii’s music history. This year marks Kamaka Hawaii’s 100th anniversary, and Fred starts the tour in the most appropriate way—with a story about his dad, which he proudly tells.

Samuel Kamaka was a musician who loved the violin, mandolin and guitar, so when he saw the Portuguese, who came to Hawaii to work in the sugar plantations, making instruments, he wanted to do the same.

“The ukulele was a simple instrument the Portuguese designed that didn’t need a case,” Fred says, his voice punctuating words for emphasis. “You stuck it under your arm, you walked down to the beach and played it, it went to parties.”

It was the instrument his dad believed to be the best choice for Hawaii. But there was a problem. Everyone back then, at the plantation camps, spoke different languages. “We ate the same food, had the same table, chairs, houses, but everything was a different wording and different language,” says Fred. His dad wasn’t sure how thick the wood should be or which woods to use, but he still tried anyway with construction lumber, only to find out it wasn’t the right wood and it didn’t produce any sound.

Photo: Aaron Yoshino

Not until a composite language was developed—known today as Pidgin English—did Kamaka figure out the correct way the Portuguese instruments were made. Soon after, in 1916, he opened up his own shop, then-called Kamaka Ukulele and Guitar Works, making high quality instruments for $5 out of koa wood—a beautiful wood native to Hawaii that delivers a great sound.

Though Fred and Sam Jr. spent many days and nights working as unpaid labor for their dad as kids (a point Fred drives hard in a funny, annoyed-son way), it wasn’t until their father became ill that they considered ukulele-making again. “He was dying and called us home,” says Fred. “He says to us, ‘I don’t know if you two want to take the business over, but remember you’re using the family name. Don’t you dare ruin that name by making junk.’” In 1953, just a few weeks after their father’s death, Kamaka’s sons decide to leave their other careers and take over the family business. “We ran the business for 46 years; nine years longer than my father,” says Fred.

In 2000, Fred and Sam Jr.’s own sons, who weren’t forced into the business like they were, and after becoming four different engineers, came to them with an idea. “They were standing where you’re standing right now,” says Fred. “My brother and I on this side [of the counter], and they made a proposal: ‘We would like to experiment because we think we can improve the way you do business.’” Everyone in the room laughs at this part of Fred’s story, and Fred explains how hard he and his brother laughed at their own kids, adding that he wanted to kick them out the door. But, Fred and Sam Jr. decided to give their sons two years to experiment. “Well, two years later, we turned the business over to our sons,” says Fred. “They have been running the business for the past 16 years.”

Photos: Aaron Yoshino

We walk outside around the corner to the entrance of the factory. The smell of wood hits us immediately; stacks of koa piled high waiting to make its way to the production line. We’re met by Fred Jr., a third-generation Kamaka, who greets us with a friendly smile, ready to show us around. The large workshop is filled with expensive computer-aided machines—the kinds of things that persuaded Fred and Sam Jr. to turn over the business to their sons. There are also a number of different shelving units, holding dozens of ukulele at a time. The room is separated into different stations based on which part of the process the ukulele is in, from when it is cut, shaped and bent to when it is tested, tuned and ready to ship. It’s set up like an assembly line, but not one that’s automated. Instead, people work on each individual piece of the ukulele with utmost care as it makes its way through the line—we catch a glimpse of the level of that detail on this tour. If a ukulele doesn’t meet the standards of Kamaka Hawaii’s quality-control tests on the floor, then it doesn’t make it upstairs, where it goes through a final sound check by Sam Jr.’s son before being delivered to its owner.

Kamaka Hawaii has grown significantly over the course of its 100 years, and it’s a real treat to hear the stories and see step-by-step how an ukulele is made on its tour. The modernized company keeps to its traditions while making advancements with technology, keeping it in the family and upholding the Kamaka name, just as Samuel Kamaka would have liked.

Kamaka Hawaii

Free tours are held Tuesdays through Fridays, 10:30 to 11:30 a.m. Call in advance to schedule. 550 South St., Honolulu, Oahu, (808) 531-3165, kamakahawaii.com.