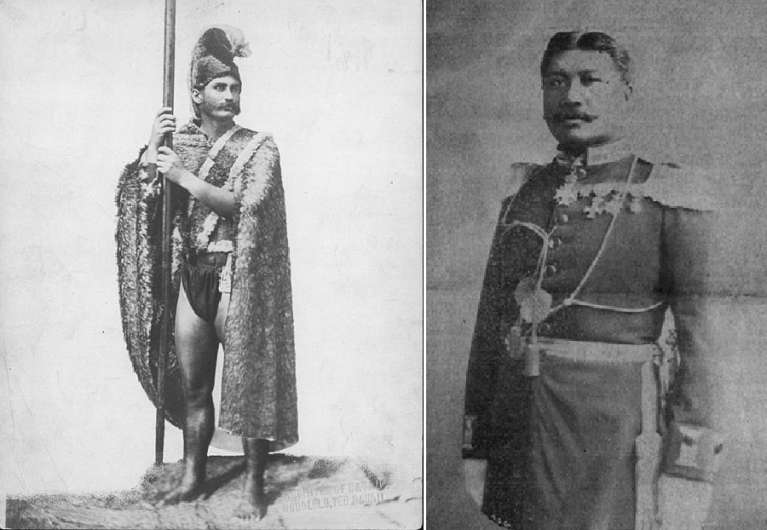

These are the two Hawaiian brothers who modeled for the iconic Kamehameha statue

John Timoteo Baker and Robert Hoapili Baker modeled for the statues you see today on O'ahu, Hawai'i Island and in Washington D.C.

Upon uniting the Hawaiian Islands in 1810, Kamehameha I laid the foundation for a strong monarchical tradition and through his governance reestablish peace and restore the economic climate of the Islands previously ravaged by civil wars. Kamehameha is credited for cultivating overseas trade and interfacing with nations outside Hawaii, but he’s also remembered for instituting laws that preserved the land’s natural resources, from prohibiting overfishing to regulating how much sandalwood could be cut from forests throughout the century.

Saturday, June 11, is Kamehameha Day, a state holiday that celebrates these achievements and foresight. An iconic statue in Honolulu—Hawaii’s most photographed work of public art—memorializing this legendary figure of Polynesia has a fascinating backstory, as recounted in the book, “The Arts of Kingship: Hawaiian Art and National Culture of the Kalakaua Era” by Stacy L. Kamehiro.

Its inception and construction reveals a lot about the Kingdom of Hawaii at the time, then ruled by King Kalakaua, whose government motto of “Hooulu Lahui” (“Increase the Nation”) was meant to instill pride in Hawaii’s people and Native Hawaiian culture as its government became a more prominent entity among the world’s economic players. Until Hawaii was forcibly annexed in 1898 by the United States, the Hawaiian Islands were an independent nation that participated in global trade, had its own currency, postage, library and museum systems, achieved near universal literacy among its citizens and thrived despite imperialistic threats throughout the 19th century.

In the face of all this modernity and new international standing, Kalakaua and his appointed Prime Minister Walter M. Gibson deemed it that much more important to commemorate Hawaii’s past by memorializing it with a permanent, public monument: The King Kamehameha statue.

In his proposal for artistic statue of Kamehameha over a lighthouse or government building, Gibson said:

“Some would appreciate a utilitarian monument … and I highly appreciate the utilitarian view, yet I am inclined to favor a work of art. And what is the most notable event, and character, apart from discovery, in this century, for Hawaiians to commemorate? What else but the consolidation of the archipelago by the hero Kamehameha? The warrior chief of Kohala towers far above any other one of his race in all Oceanica [sic]. His character, in view of his remarkable situation will ere long largely command the attention of thoughtful and noble minds of all lands. The appreciation of his character I hope to promote with my feeble pen; and his fame will be praised as a proud memento for Hawaii. Therefore let Hawaiians, especially you Hawaiian Nobles and Representative, lift up your hero before the eyes of the people, not only in story, but in everlasting bronze. Thus enlightened nations commemorate their heroes and good men.”

Gibson sought a classically trained sculptor, Thomas R. Gould, believing that fashioning the statue within the authority of the Euro-American academic tradition would attract the admiration of the world’s nations. That said, the iconography of Kamehameha is unequivocally rooted in Hawaiian history and culture. For Kalakaua and his advisors it was paramount to assert that the hero of the century of this land was not a foreigner, but a Native Hawaiian. That Hawaii’s most celebrated public figure for the rest of the world would be kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) and not, for instance, Captain Cook. The statue may be utilizing Western visual language, but the narrative it expresses is intentionally not: It is Hawaiian.

Authenticity was a priority for the statue’s design with Kalakaua and Gibson directly involved in the preliminary stages of it. Kalakaua personally provided sketches and suggestions for the musculature of the body, in addition to drawings and photographs of Hawaiian spears and a watercolor portrait Kamehameha sat for just three years before his death.

Photo courtesy Hawaii State Archives (left). Photo by Prayitno/cc (right).

To aid the artistic process, the Monument Committee sent photographs of Hawaiian men who fit their representation of what was believed to be Kamehameha’s admirable physique. They also included photographs of John Timoteo Baker, the last royal governor of Hawaii, fitted in royal adornments to help realize the statue’s royal ahu ula (feather cape), mahiole (helmet) and its rare kaai (feather sash).

The image above at left is believed to be a composite image. From the torso up is Baker; the legs belong to Baker’s brother Robert Hoapili, who had the more athletic physique. Hoapili served as aide-de-camp to King Kalakaua and later Royal Governor of Maui from 1886 to 1888.

The two brothers served as the chief models for the statue you see today on Oahu, Hawaii Island and in Washington D.C. and these photos serve as a reminder behind the intensive and thoughtful process behind the now internationally recognized symbol of Kamehameha the Great.